Cameroon’s early-00s kits weren’t just uniforms; they were provocations.

In 2002 and again in 2004, the Indomitable Lions and their supplier used the global stage to test the edges of football’s dress code. The result: two of the most talked-about designs in the sport’s modern history - and two swift rebukes from FIFA that helped define where “innovation” ends and “infringement” begins.

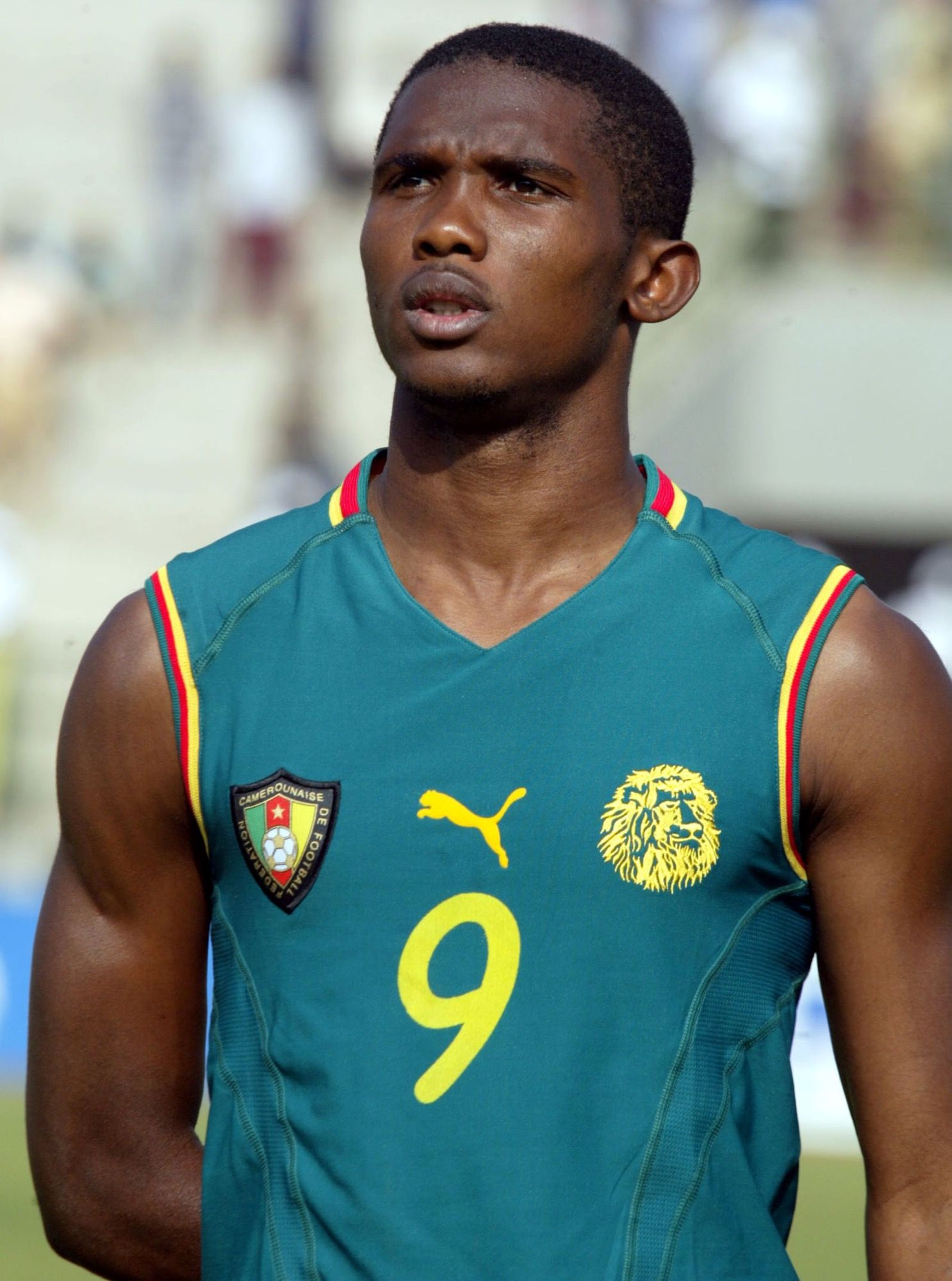

First came the 2002 “sleeveless” shirt, a basketball-style vest worn at the Africa Cup of Nations. In isolation, it was clever and clean: deep green body, sculpted armholes, and none of the flappy fabric that defenders love to tug. FECAFOOT (Cameroon’s federation) approved it, and Cameroon wore it all the way through the tournament. But for the World Cup that summer, FIFA said no. The official line wasn’t about aesthetics - it was logistics and regulation: tournament sleeve patches had nowhere to go on a shirt without sleeves. Cameroon ultimately added black sleeves to satisfy the rules, a compromise that preserved participation but blunted the original design’s “shock value.” Even so, the vest remains a cult artefact precisely because it dared to treat football kit conventions as optional.

If the sleeveless top was a nudge, 2004 was a shove. For that year’s Africa Cup of Nations, PUMA introduced a one-piece kit - essentially a zip-up bodysuit in Cameroon’s red-green palette. The logic was performance-driven: remove bulk, streamline the silhouette, and make it harder for opponents to grab. It was also a statement about what a “football shirt” could be in an era when fabric technology and athletic fashion were merging. The problem? FIFA moved to clarify the boundary in real time. Then-president Sepp Blatter underscored a fundamental requirement: shirts and shorts must be separate garments. Cameroon wore the suit at AFCON anyway, making their point on the pitch - but the regulatory backlash was severe.

The sanctions were unprecedented in their bite for a kit infraction. FIFA fined Cameroon (reported at CHF 200,000 / roughly £120k at the time) and docked six points from the team’s 2006 World Cup qualifying campaign - punishment that risked competitive disadvantage well beyond a single tournament. The message was clear: FIFA would enforce not just how kits looked, but how they were constructed.

What’s striking is how quickly those two episodes reframed the conversation around kit design. Before Cameroon, the frontier in shirt innovation was mostly about graphics, crests, collars, and fabric technology. After Cameroon, construction itself - sleeves vs no sleeves, two pieces vs one - became part of the aesthetic battlefield. And FIFA’s response effectively became part of the design brief: any audacious concept now had to anticipate not only performance and look, but the letter of Law 4 and tournament regulations (including the seemingly mundane requirement to host competition patches). The 2002 ban, grounded in something as unsexy as patch placement, is a perfect example of how small administrative details can steer big creative choices.

Culturally, both kits fit Cameroon’s identity as expressive, boundary-pushing trendsetters. The country had momentum - AFCON titles, a global fanbase charmed by their swagger - and the shirts extended that charisma into fashion. The sleeveless top telegraphed athletic confidence; the bodysuit was almost futurist. Even PUMA’s own retrospective storytelling frames the UniQT suit as a fearless experiment designed to reduce grabbing and modernise the game’s silhouette. You don’t have to love the look to appreciate the nerve.

Legacy is where the story gets interesting. In the short term, Cameroon complied - sleeves were stitched on in 2002, the one-piece disappeared after 2004 - and FIFA established a precedent that still governs kit construction. In the longer arc, those “banned” kits became folk heroes: constant fixtures in “greatest/strangest kits” lists, pricey collectables on eBay, and reference points whenever a brand touts a cutting-edge concept. Even news and culture pieces years later still cite the sleeveless ban as a turning point for kit culture. The result is paradoxical: FIFA’s pushback arguably amplified the myth of these designs, turning what could have been short-lived stunts into legends.

In the end, Cameroon’s 2002 and 2004 kits matter because they forced a conversation about what a football kit is supposed to be - strip, costume, performance tool, or canvas for invention. FIFA reasserted its custodial role; PUMA and Cameroon proved that even a regulatory “no” can reverberate as a cultural “yes.” Two decades later, every unusual collar, fabric map, or structural tweak still lives in the shadow of those sleeveless armholes and that zipped seam. That’s a remarkable afterlife for a pair of shirts (and a suit) the game wouldn’t let play by the rules.

We also think you'll like...